Yesterday, I swallowed a radioactive pill. If I don’t already have cancer, by golly, they’re going to give it to me. Those of you who know me will appreciate just how far from the shore I have drifted when I tell you that, because you know, usually, I don’t even take ibuprofen lightly.

The medical assistant brought me through the maze of the hospital to the nuclear medicine department, and sat me down in a little, tiny room (possibly a repurposed closet?). She carried the pill in a canister, similar to that which is used to send money back and forth at a drive through bank. Inside, there was another tube, and inside that, a vial, and nestled inside of that, was my neon green capsule, tucked in like the littlest baby inside a Russian Doll.

She used gloves as she got down to the business of freeing the tablet from this complex containment system. I noticed the way she carefully avoided touching the pill, using only her fingertips to take the cap off the inmost vial, which she then handed over to me, instructing me to drop the capsule straight into my mouth without touching it. (I would like to mention here that she was quite pregnant. Just as an aside.)

“Don’t worry, there are no side effects,” she said, making sure not to let her fingers come into contact with the inside of the now-empty vial. This, she secured back inside the tube, then placed it back into the canister.

Flush the toilet twice after urinating for 24 hours after your RAIU (Radioactive Iodine Uptake) test, to prevent radioactive material from sitting in the toilet, the informational pamphlet said. For the record: I completely forgot to follow this instruction, and my toilet is doing just fine. (I’m not sure about me, or the fish downstream off the Gulf Coast, but come to think of it, that’s a dead zone anyway.)

That was all I had to do on day one of the test. On day two, I’m to return for the scan, which will measure the uptake of the radioactive iodine by my wayward thyroid and tell us whether there’s a foot leaning too hard on the gas (hyperthyroid), or if we have an engine that won’t turn over (hypothyroid).

We already know I have thyroid nodules — just one of the many problems discovered in 2023: The Year of My Odyssey Through the Medical Industrial Complex. This journey has been a fascinating study of the state of Humanity as it relates to bodies, and the treatment thereof. So far, my reward has not been to feel any better, but to have a head spinning with a small medical degree’s worth of new information.

Regarding my thyroid, my symptom picture is confusing. We are conducting this bizarre test with the hopes it will shed some light, and help us get to the bottom of what’s going on.

The various weirdnesses I am experiencing could assign to me to either camp: hyper or hypo. The racing heart pounding loudly in my ears, really fun adventures with temperature dysregulation, and a low TSH blood value all point to hyperthyroidism. But the weight gain, the fatigue, and the depression — these all seem more consistent with hypothyroidism.

And about the weight…

Before I was in my mid-thirties, I could barely tip the scale to 100 pounds. My only concern with body fat was not having enough of it. I know, I know — no one wants to hear this type of complaint, but it was real! I was the kind of skinny that people can’t help but to comment on. My body image suffered just as much as if I had been extremely overweight.

Not that everyone is by any means kind enough to follow it, but it’s a widely accepted societal norm that it’s not polite to comment on people’s extra weight. I’m here to report that no one ever held back about my thinness.

You’re like a stick figure. You’re as skinny as a rail. You’re a wraith. You need to put some meat on those bones. You must eat like a bird.

Or, as my former mother-in-law from Brooklyn kindly put it during one of our torturous visits, I think maybe you’ve gained two ounces. You almost have a fig-yuh!

I never, ever thought I’d see the day where I’d have concerns about too much weight.

Then middle age happened.

As it seems to be the rule that a woman should never accept her body as it is, let alone be happy with it, I’ve been bumming out about my disappearing waistline. The other day that changed, and I’ll get to that, but this is all second page news.

I know there are those of you following along who are waiting to hear the main headlines: an update about the breast issues I’ve written about recently, so I will get to that now. (Thank you so much for caring, by the way, and reading this far.)

I had breast surgery almost a month ago to remove two masses that showed Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH) on biopsies. That finding catapulted me into a 40% lifetime risk for breast cancer.

It has become clear from all of the many types of imaging and testing I have undergone, and from the pathology report that followed the surgery, that I have no less than four types of masses, and MANY of them. So many, the MRI report didn’t even specify a number. It just said “many.”

Luckily, ADH is as far as things have progressed, with regards to cell mutation. So, I’m very glad to report that no one is saying I have cancer. This is extremely good news! I had been dreading that the atypical findings from the biopsy could be upgraded after further study, and was scared I might need radiation or chemo. So that comes as a huge relief.

However…

I do have an advanced case of ductal ectasia, which is a non-cancerous disease of the milk ducts. They’re widened terribly, filled with gunk (medical term), are extremely inflamed and very painful. My doctor said that during the surgery, when she cut into the ducts, there was a flood of brown fluid that poured out, which wouldn’t quit making a mess of things, no matter how much she suctioned up. She thinks this condition is probably what has been causing the relentless infections I’ve been getting since August.

In fact, I blew up in an infection the very day of surgery, and this, she says, “Just doesn’t happen.”

Well, it happened to me.

But let me back up. This was breast surgeon #2. I fired breast surgeon #1 a week before the main event, when I went to #2 for a second opinion, and decided to switch horses on the spot.

#2 has thirty three years of experience in this field, whereas #1 was maybe thirty three years old. Nothing against young doctors, but my new surgeon’s experience really shows. I hadn’t realized how wrong I’d been feeling in the care of #1 until I tasted something new. I didn’t love how she spoke down to me, rushed my appointments, and didn’t provide satisfying answers to my questions. I didn’t appreciate her condescending tone, or the way she rolled her eyes a little when I asked if we could please try to get to the bottom of the infections, and rule out inflammatory breast cancer with a simple test at the time of the surgery.

No, I wasn’t particularly comfortable with any of this, but the kicker, and ultimately, the deal breaker, was when she said she wanted to schedule me an appointment to have two radioactive seeds placed in my breast.

These, she explained, would be installed in a procedure that was essentially just like a biopsy, only in reverse. Using ultrasound guidance, a needle would deposit two grain-of-rice sized, radioactive “seeds” a week before surgery, to help guide her to the problem areas in the operating room.

What the hell, you may ask, as I did. And I think we are right to ask.

“Not to worry,” the nurse said. “There are no adverse effects.”

Well, I did worry. A lot. Especially when I read that I should not hold babies or young animals any longer than thirty minutes, once a day, for the duration of the time the seeds were implanted.

And there was this: just a few weeks before, at the time of the biopsies, I developed a raging infection before the end of the day. In that case, something (tissue) was being taken out, rather than something (radioactive seeds) being put in. But as #1 said when I brought my very infected breast in for an exam, my boobies do not like to be messed with!

So now I was losing sleep, running through nightmarish scenarios, and breaking down in tears left and right. Everything felt wrong. I was sure that if I allowed her to place these scary seeds inside my body, my breast would blow up (again). Then they would say, “Sorry, but we can’t operate on an infected field.” And there I’d be, just waiting around, turning green, or growing a second head or whatever.

No thanks.

When I went to get a second opinion from #2, she was shaking her head before I even got done telling her about this plan. She said I was not a candidate for the seeds, given my history of infection.

What she would do instead would be to place wires on the morning of the surgery. This way, my body would not have time to react with an infection. I would start the day at the imaging center where, under mammography and ultrasound, thin wires would be guided through needles to the two problem areas. I would leave this office with the wires hanging out of my boob, coiled up, and taped to my skin, and drive straight over to the surgery center. There, she would remove them and the offending tissue they led down to, all in one fell swoop.

“OK, sign me up,” I said, and booked my appointment.

When the day arrived and it was time to go through with it, I only had a minor emotional breakdown in the dressing room. My husband held me through the thin gown while I cried.

“It’s not too late,” he said, “You can still change your mind.” To which I said no, I could not, or else, believe me, I already would have. He understood, and let me keep crying. And I knew what his heart had meant when he’d said it.

Then I put on my big girl pants (well, technically, they were already off), and faced the music.

At my follow up visit, the surgeon explained that, with the many masses in both breasts that have a very significant chance of turning into cancer, and therefore could not be ignored, as well as the severity of the ductal ectasia, and the constant infections, she had to recommend a double mastectomy.

“I know, I’m sorry. I know,” she said sympathetically when I cringed. “But you can have reconstructive surgery. Probably even immediate reconstruction!”

The thing is, she went on, now that I am considered high risk, what with the atypical cells my body has begun to make, I would likely have to go through this kind of thing every six months, going forward. Because my breast tissue is very dense, it makes it hard to catch cancer with routine imaging. If I keep my breasts, I will have to have an MRI every year, and six months after each MRI, a mammogram with ultrasounds. She warned that each time, they would likely come back with recommendations to do more biopsies and surgeries like what I just had.

“The worst part is,” she said, “You could go through endless rounds of this, and we could still miss cancer.”

Since the infection that immediately followed surgery, I’ve finished round six of antibiotics for the year (seven, if you count the IV antibiotics used during surgery), but my pain has not gone away. Thankfully, the horrific stage of having a Boob of Many Colors has passed. (This was like Dolly Parton’s coat, only not so pretty). I finally got the stitches out, and my breast is down to a dull roar, as far as discoloration. It’s starting to look less like one of Frankenstein’s creations.

Oh, but the story is not over. On New Year’s Eve my incision started leaking. The icky brown fluid found a new pathway, and now, if I don’t wear a pantyliner in my bra, it looks like I’ve spilled betadine on my shirt.

Fun times.

New Year, New You! That’s what everything around us seems to be falsely advertising. But here I am, Same Me. I had five medical appointments in three days during the first week of January, including a return visit to the breast clinic so the surgeon could swab the creepy fluid. She sent it off to culture, and put some on a slide to check for cancer cells.

The cytology slide hasn’t produced any results yet, but yesterday, the swab test came back showing MRSA. This will require further investigation, and yet another office visit as soon as the flood watch and tornado warnings are lifted (!). We will aspirate some of this fluid with a needle, if we can find a pocket of it with the ultrasound, to get clearer about whether the MRSA the swab picked up was from my skin, or if there’s a current infection brewing in — what? My blood? My tissue? This fluid? I don’t even know.

I’ve taken way too many antibiotics, which is probably (almost certainly) how I got here. But what else is one supposed to do with raging cases of mastitis that don’t respond to natural remedies? Become septic and die?

Meanwhile, I’ve been shopping for new breasts. This is just another strange pastime we’ve come up with in the 21st century, and it’s a very confusing process, indeed.

“Fuck the patriarchy and boob idolatry! It’s absurd how these round protrusions from our chest become so much of our visual identity,” a dear, and very sympathetic friend said recently when we were discussing this.

And while, I couldn’t agree more, I’ve decided I do want breasts, if for no other reason than just sensing I would not feel whole without them. I can learn how, if I have to, but I think this transition will be easiest for me if there’s not a gaping cavern where my chest used to me. Waking up from surgery with ribs showing through my chest skin sounds traumatizing. So if I can help it, I’d like to try and continue to have boobs.

Here are the choices: Implants, or DIEP Flap reconstruction, or a combination thereof.

After much exploration, consultations, and horror stories on Facebook support groups, I have too many concerns about implants. I realize that the problem with online forums is that they are mostly populated by people who are having a terrible experience, but I’m going with my guts on this.

Unlike cosmetic breast enhancement, wherein implants are placed behind the breast tissue, a double mastectomy leaves no breast tissue. Therefore, reconstruction with implants means the silicone blobs sit just underneath the skin. Cold and hard and weird, with edges and ripples showing, I think these could wind up being like Barbie Boobs, and I’m quite sure I wouldn’t like them. Not to mention, having two autoimmune conditions, I am concerned about putting foreign objects in my body. It doesn’t need anything else pissing it off — it’s got enough to contend with. So I’ve crossed implants off the list.

I’ve opted instead for the DIEP Flap. And oh boy, talk about Frankenboobs!

This surgery is likely to take at least eight hours (for my friend it was 11), and will involve three surgeons. The breast surgeon will perform the double mastectomy. Then the plastic surgeon will step in.

He will cut a big eyeball-shaped section of skin and fat and vessels out, from just above my belly button, to just below my underwear waistband. He will use this tissue to build me new breasts.

A microsurgeon will carefully reattach the vessels, so that the relocated tissue might live, in particular the deep inferior epigastric perforator artery, for which DIEP is named.

Then, the plastic surgeon will close the gaping space on my belly, producing a result that’s essentially something like a tummy tuck. This will leave the hand-stitched, patchwork quilt, previously knows as my torso, with a scar that runs across my belly from hip bone to hip bone. Triangular flaps, one for each boob, made out of the big eyeball shape of flesh now missing from my belly, will be sewn in where my breasts have been removed, to create the new, 2024 model. New Year, New Me.

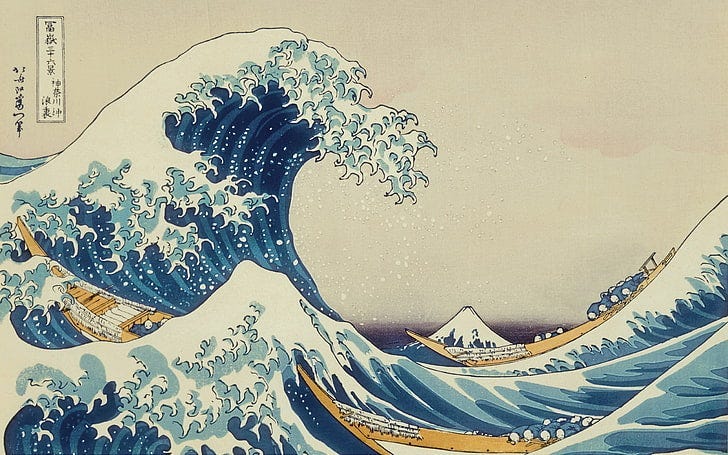

I’m always one to keep things festive, so to add interest, the big tattoo I have on my belly — a reimagining of Hokusai’s famous Great Wave, with a couple of Japanese koi fish swimming in it, will be chopped up and rearranged. Parts of this artwork will come to rest on my chest. A fish tail will comprise one of my new nipples, and I’m pretty sure the deepest part of the Wave of Kanagawa will lie right over my heart. Rising up from my belly scar will be the tops of the wave and droplets of water that are, at present, hovering over my belly button. And speaking of belly buttons, they will be making me a new one.

Perhaps the strangest thing to me in of all of this is that, with the removal of my original connection to my mom (the umbilicus), and the tissue that produced milk for my babies, significant monuments to motherhood will be erased from my body. I realize that some pretty deep mother-wounds have defined my life, but this is really taking things to the next level.

The plastic surgeon says that since I don’t have a lot of fat to work with (contrary to my opinion of late), my new breasts may have to be a bit smaller than they are now, and I’m ok with that. I’d rather have natural looking smaller breasts that are warm and human, than weird plastic big ones.

This brings back around me to how, ironically, it suddenly seems I could almost use more belly fat to work with, now that it is being repurposed — which is just further proof that we are never satisfied with our bodies.

But no, really, I joke — I am fine with being a bit smaller up top. The main thing is to feel healthy and whole. If anything, when this crazy thing is over, I may opt to go back to the drawing board with a tattoo artist to figure out a new design for the butchered tsunami wave. While I am very much not looking forward to the nerves being cut, and my chest being numb for the rest of my life, I guess for the purposes of applying new ink, that might come in handy.

But that will all happen further down this long, winding road. Frankenstein’s monster has got nothin’ on me!

Photo credit: https://c4.wallpaperflare.com/wallpaper/975/543/797/the-great-wave-off-kanagawa-painting-waves-japanese-wallpaper-preview.jpg

Thank you for writing.

I am in awe of your sense of humor in the face of all this. Remarkable.